Africa is a continent with a serious financing gap. According to the African Union, ‘Africa’s sustainable financing gap until 2030 is about $1.6 trillion,’ and ‘the continent needs additional financing of about $194 billion annually to achieve its Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. This financing gap is equivalent to 7% of Africa’s GDP’.

To address this gap, Africa must increasingly prioritise self-reliance and gradually reduce its dependence on international aid, especially as global dynamics continue to shift. Central to this transition is the need for African nations to mobilise more of their own resources through taxation, investment, and sustained economic growth, while also boosting intra-African trade to strengthen regional integration and unlock shared opportunities.

One of the most promising and underutilised instruments in this domestic resource mobilisation effort is excise taxation. Excise taxes serve not only as a vital tool for revenue mobilisation, but also as a strategic instrument for shaping consumer behaviour. In the case of health- tax products such as alcohol, tobacco, and sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), excise taxes have proven to be both cost- saving and effective, making them essential tools for achieving fiscal and public health objectives.

According to the ATAF publication ‘African Tax Outlook1’, the average contribution of excise taxes to total revenue in Africa is around 8%. In many African countries, most excise revenue is derived from fuel, alcohol, and tobacco, although this varies across the continent.

Recently, there have been innovative developments in excise systems, with excise taxes extended to a broader range of products, such as cement, cooking oil, sugar and nonalcoholic beverages.

For instance, Ghana applies a zero-rated excise on textiles – not as a revenue-raising measure but to protect local industry. The excise is applied by means of tax stamps affixed to the textiles. Similarly, some countries have introduced zero-rated excise on pharmaceutical products, using the measure as a regulatory tool rather than a fiscal instrument.

In many African countries, excise duties are also applied to services such as telecommunications and financial services. Furthermore, there is an increasing discussion around the betting and gaming sector, where many African tax administrations are considering appropriate taxation and regulatory controls – viewing excise taxes as an effective tool for both.

These various excise taxes are capable of generating reliable revenue streams. Since excise is often collected at manufacturer or import level, the administrative burden of collecting it is reduced, and enforcement is made more manageable... in theory!

In practice, however, the picture is somewhat different. Given that excise tax is increasingly being levied according to weight, quantity, product content or volume, rather than value, it places a significant tax burden upon each taxable product, even those that cost relatively little to produce, such as SSBs. If excise tax can be avoided or evaded, it provides a substantial commercial advantage in the marketplace, along with increased profitability. Thus, excisable goods have a long history of attracting illicit activities such as smuggling, as well as taxpayers who attempt to understate their tax liabilities.

The latest illicit trade report by the World Customs Organisation says tobacco and alcohol are among the products with the highest levels of illicit trade. As far as Africa is concerned, these levels vary considerably between countries. According to the 2023 edition of African Tax Outlook, cigarette illicit trade ranges from well over 50% in South Africa to 5% in Kenya.

At this point, I want to ask you a question. Who do you think is pictured above?

A customs officer, right? Traditionally, this type of officer is deployed in many countries to undertake tasks such as production monitoring and other excise control functions.

However, in today’s environment of automated factories and complex manufacturing processes, relying solely on physical officers for excise control is no longer effective.

This challenge requires a new approach – one where technology offers practical solutions to many of the issues surrounding excise administration and control.

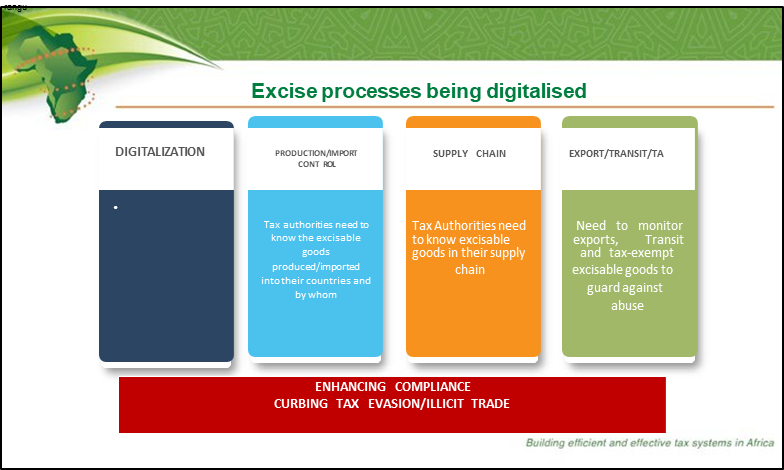

One of the key discussions emerging today concerns the digitalisation of excise taxes, as tax administrations increasingly seek to digitalise their excise processes and implement technologies that enhance control over critical areas such as production, import and export of excisable goods, and supply chain controls.

In the image above, the tax processes listed in the left column have already been automated in many countries. Where automation is not yet in place, it is strongly recommended. The main challenge now lies in addressing the controls listed in the other three columns, and ensuring that the systems managing these controls are integrated with other tax systems.

In many countries where control systems – such as tax stamps – have been implemented, these systems tend to operate in silos. If properly integrated, tax administrations could gain access to a comprehensive dashboard with matching – or non-matching, as the case may be – data spanning the entire excisable goods ecosystem.

While viable solutions exist to digitalise excise processes and manage the controls highlighted above, many African countries face significant implementation challenges. Cost remains a major concern, as these systems can be expensive to deploy. As such, innovative financing models need to be explored to support their adoption.

There is also an issue with technical expertise, not so much in terms of knowledge transfer – because once a system is implemented, knowledge transfer can easily occur as part of the rollout process – but more in terms of the technical gap that exists at the procurement stage.

As a result of this gap, government officials involved in the procurement process often don’t know what solutions are out there, so don’t know what to ask for. This is why an event such as the Tax Stamp & Traceabiity Forum™ is important, in that it allows government authorities to familiarise themselves with current technologies and best practices.

Other key challenges include infrastructure limitations, advances in illicit trade methods, and weak enforcement systems.

To address these and other challenges associated with the implementation of excise technologies, ATAF highlighted several key recommendations for countries to consider. A few of these are outlined below:

The African Tax Administration Forum (ATAF) is a pan-African intergovernmental organisation that brings together 44 member countries with a shared commitment to improving tax systems across the continent. ATAF serves as a platform for cooperation, knowledge exchange, and capacity development in tax policy and administration. Through tailored technical assistance, strategic policy support, in-depth research, and high-quality training programmes, ATAF empowers African tax administrations to enhance domestic resource mobilisation. The organisation also produces practical toolkits, policy briefs, and thought leadership materials to inform reforms and promote fair, transparent, and effective tax systems that support sustainable development in Africa.

Linstrom Marangu can be reached at lmarangu@ataftax.org.

1 - events.ataftax.org/includes/preview.php?file_id=243&language=en_US