Whether you use tax stamps or you don’t use tax stamps, let’s face it, illicit trade still exists. The difference is, tax stamps and associated track and trace and production monitoring systems help make illicit trade stand out more (like a sore thumb), plus they make it easier to trace illicit trade back to its origin, and identify at what point in the supply chain legal trade may have become illegal trade.

What’s more, real-time production monitoring systems have been proven to reduce some forms of illicit trade, including under-declarations by taxpayers and round-tripping, as we will see in one of the following country cases.

But let’s start with some country experiences that demonstrate how tax stamps shine a light on non-compliant product, even if it’s just by their very absence.

Take the Philippines, for instance. They have been using tax stamps on cigarettes for a number of years now – extending to alcohol in 2022. While illicit trade remains a constant problem in the country, the stamps serve as an essential aide for the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) to identify illicit product during their market inspections and nationwide raids.

During one such raid this year, for example, the Bureau confiscated several bottles of alcohol and boxes of cigarettes worth millions of pesos, with most products bearing Chinese characters (which is also a visible indicator of illicit product). But, in addition, all of the products were missing excise tax stamps, thereby providing irrefutable proof of non-compliance.

Furthermore, one store selling expensive wine had the excise stamp on the side of the bottle rather than placed over the opening of the bottle to prevent reuse. Such placement is against Philippine regulations, and, again, provides clear, visible proof of non-compliance that could be used as evidence for case filing.

The takeaway here is that if BIR officers had not been able to rely on tax stamps to determine clear, yes/no compliance, their task of weeding out illicit product would have been made that much more difficult.

To the next example… all the way over in Pennsylvania, USA, where it was reported in September that an increasing number of charges of possession of unstamped cigarettes were being filed by state police.

By law, each Pennsylvanian may possess up to one carton of cigarettes not bearing state cigarette tax stamps. However, the purchaser is still responsible for paying Pennsylvania taxes on those out-of-state cigarettes.

The proximity to the Allegany Territory of the Seneca Nation of New York was given as the most likely answer as to where the cigarettes were being purchased from. Because the Nation is sovereign, cigarettes there do not include the New York tax of $4.35 per pack (and therefore do not carry tax stamps), so prices are notoriously low.

A Pennsylvania (PA) police station commander, based at Lewis-Run station, 30 minutes away from the Allegany Territory, said the station was doing its job looking for illegal cigarettes, but that there was no real crackdown happening. ‘When the guys are out, they are definitely looking at it. If there’s a whole lot of cigarettes in a vehicle in plain view, they will inquire about it,’ he explained.

According to the state Department of Revenue, possessing one to five cartons of unstamped cigarettes could incur a $300 fine and/or up to 90 days in jail. And selling one or more packs of unstamped cigarettes could incur a fine of $100 to $1,000 and up to 60 days in jail. The wrongdoers are also at risk of having their vehicle seized if they are carrying more than 10 cartons of unstamped cigarettes.

The case of Pennsylvania provides another example of how enforcement officials depend on the presence or absence of tax stamps to determine the legality of products.

For the final example, let’s go to Chile, where a recent report by economics academics, working on behalf of Bloomberg Philanthropies, showed that Chile’s tobacco traceability and production monitoring system, introduced in 2019, led to a 16% increase in tax collections between 2019 and 2021, thanks to the ability of the system to give the tax authority real-time visibility into the number of cigarettes being produced in each of Chile’s tobacco factories.

This improved visibility is what reportedly led to a significant reduction in the illegal practice of ‘roundtripping’, where products are manufactured and designated for export, then exported in order to avoid domestic taxes, and subsequently smuggled back into the original jurisdiction, potentially avoiding several excise taxes.

The report further claimed that the drop in exports could also have been due to the presence of the unique traceability mark (as opposed to paper-based tax stamps) which is applied to all cigarettes intended for the domestic market, thereby making any illicit re-entry of these products more difficult.

A full article on the Chile report is on page 4 in a separate article this month.

These three examples show that having tax stamp, track and trace and production monitoring systems in place facilitate detection of illicit trade, and actually stomp out certain types of such trade, thereby increasing tax revenues.

But these systems need to be used in conjunction with robust enforcement and prosecution regimes, otherwise, in themselves, they’re not going to be of much use… much like any other regulatory instruments which are in place but not enforced.

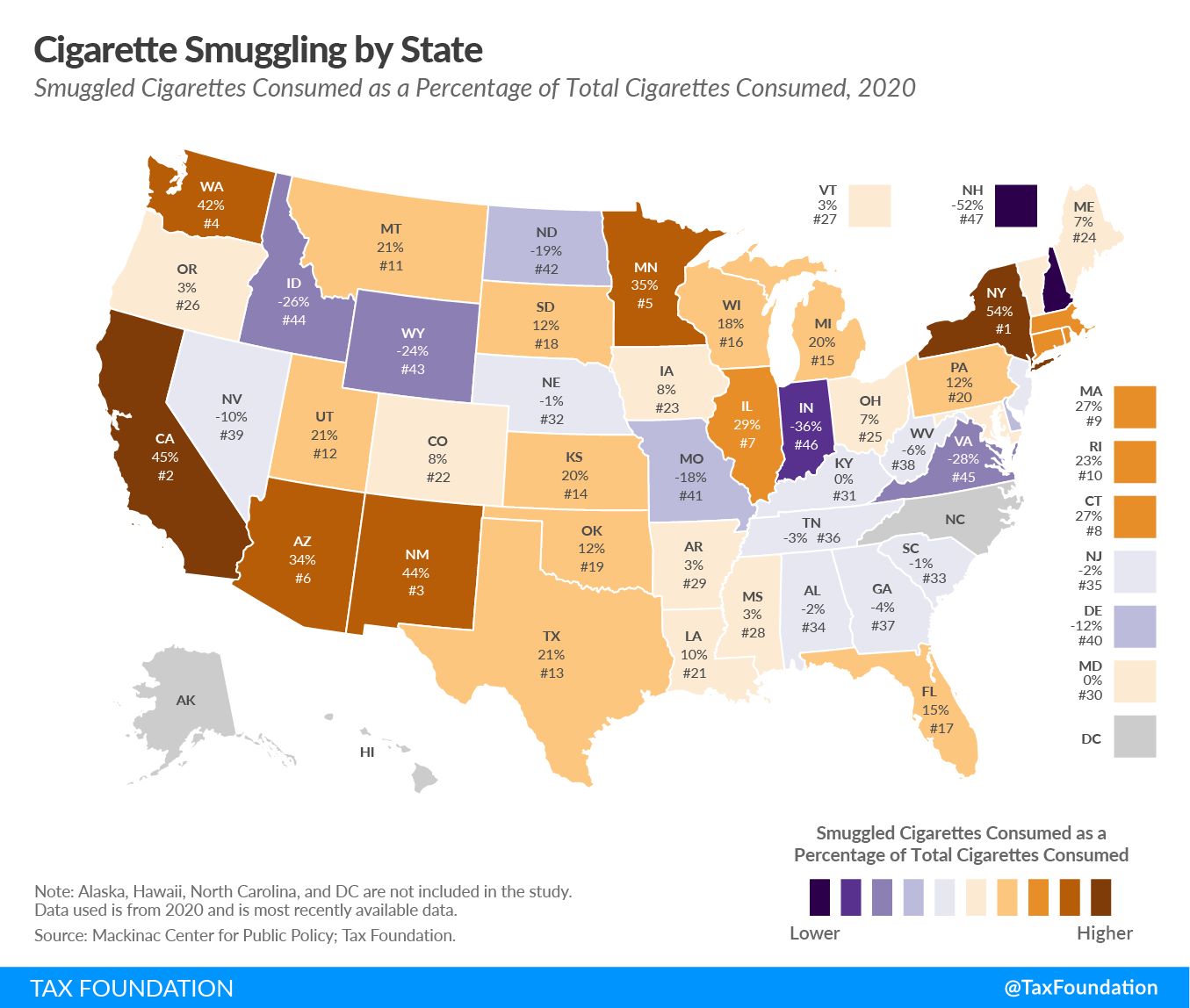

Map from Tax Foundation illustrating smuggling levels per US state.