The third session of the Meeting of the Parties (MOP3) to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products will take place on 27-30 November in Panama, and the provisional agenda has now been released.

Of particular interest for the tax stamp and traceability community is an agenda item dedicated to track and trace systems and the global information-sharing focal point (GSP) required under Article 8 of the Protocol. The MOP3 discussions around this topic will be based on a report 1 issued by its Working Group on Tracking and Tracing Systems. The group was established by MOP1, back in 2018, for developing and implementing track and trace in accordance with the Protocol.

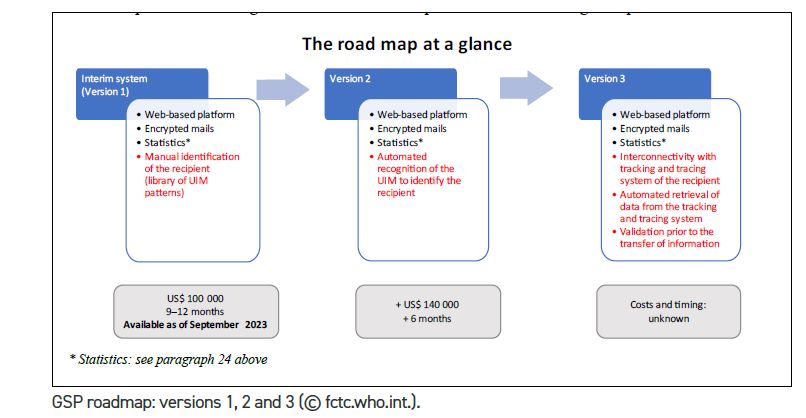

The report includes recommendations relating to the further development of the GSP, an interim version of which will be implemented in September 2023 at the FCTC Secretariat in Geneva, Switzerland. September 2023 is also the date by when two thirds of the 67 parties to the Protocol should have a tobacco track and trace system in place.

The interim version of the GSP is designed to have minimum impact and be technologically neutral, in order to facilitate adoption by all parties. The report recommends that any developments beyond the interim version should be proportionate to actual usage and available resources of the parties, given that the interim version already complies with Protocol obligations.

The interim (version 1) solution for the GSP is intended to be an end-to-end encrypted messaging system to enable parties to exchange traceability data against unique identification markings (UIMs) found on tobacco products in their territory. This solution is expected to be tested by some parties in 2023 and to be ready for parties to use from September 2023.

Parties are expected to provide the Convention Secretariat with information on their UIM code pattern, which will be used to create a manual library of such patterns. Upon finding suspected illicit tobacco with unrecognised UIM codes within their territory, parties can consult the library to identify the party most likely to be responsible for issuing them.

Parties will use the encrypted messaging system to send a message to the party identified as responsible for the manufacture of products. That message will consist of the UIMs in question and fields for asking additional questions. The receiving party will consult its traceability system to identify if the UIMs were created within that system, and then send a response to the requesting party confirming whether the UIM is valid. If valid, the receiving party will also provide traceability data linked to that code, such as manufacturing details and intended shipment route.

More advanced versions of the GSP will build on the interim system, in that they will continue to operate through a web-based platform through which encrypted emails are exchanged between a requesting and receiving party.

Version 2 of the system intends to facilitate the process for requesting information. To this end, it would contain a tool where UIM patterns – and subsequently the party issuing those patterns – are automatically recognised. Therefore, the requesting party no longer has to manually verify UIMs against the library of patterns, as is the case in version 1. However, both versions 1 and 2 require a manual process for the receiving party to download the request, process it in its tracking and tracing system, generate a reply from this system, and send this reply through the GSP.

As for version 3, this would simplify the process for replying to requests, by building on version 2 and including interconnectivity between the GSP and track and trace system of the party with whom the seized product is registered.

Such developments would require that a substantial number of parties be in a position to benefit from the system and actually use it. Since only a limited number of parties have so far implemented fully-fledged national/regional track and trace systems, this would not currently appear to be the case.

The number of parties with track and trace systems in place is a key criterion for justifying the need and usefulness of a more advanced GSP. The more tracking and tracing systems are in place, the more seized tobacco products are likely to bear the UIMs required under the Protocol, leading to more requests via the GSP to the parties issuing those UIMs.

To this end, the working group calls for quantitative and qualitative criteria to be put in place for assessing the need to move to more advanced GSPs. Apart from the number of systems in place, these criteria include the percentage of parties actually sending and receiving requests via the GSP. The working group recommends that if 50% of parties (ie. 33 of them) are doing this, then a move to version 2 of the GSP should be considered.

The group therefore stressed the need for automated usage statistics to be produced by the interim GSP in order to monitor the situation.

With regard to the nature of national track and trace systems themselves, apart from the regulations laid out in the Protocol, no other technical specifications appear to have been implemented as mandatory requirements. Therefore, the parties are free to implement their programmes according to their specific national or regional needs, as long as these fall within the framework of the Protocol.

So, rather than being mandated to come up with a list of technical requirements (similar to those issued by the European Commission as a supplement to the EU Tobacco Products Directive), the Working Group on Tracking and Tracing Systems was instead mandated, in 2018, to compile an overview of good tobacco track and trace practices already employed by parties. This it did by sending a questionnaire to parties to the Protocol as well as parties to the broader WHO FCTC.

A total of 16 responses to the questionnaire were received from WHO FCTC parties, of which 11 were also parties to the Protocol. Out of these, one response was received from the European Commission, representing 18 parties to the Protocol that had implemented a single regional track and trace system.

The findings were presented at MOP2, in November 2021, and included:

Some parties required the tobacco industry to bear the full costs of implementing the system, while in other instances public resources were used. In at least one case, licensing fees were indicated as the main proposed source of financing for the system.

Responsibility for implementing the system was in almost all instances distributed between the ministry of finance, customs, and ministry of health.

No pattern could be identified in relation to the use of UIMs for tracking and tracing tobacco products. Some parties delegated the development of unique identifiers to a specific national entity, while in other cases the contractual partner engaged for the establishment and routine management of the system was responsible.

Security features used to protect the integrity of the UIMs included, among others, number serialisation, time stamps, and QR codes (no mention was made here of physical security features).

In most instances, parties reported that data produced via the system was ready for export, but not in all cases ready to be accessed via the GSP platform. Generally, data was accessible for inspection by law enforcement agencies and regulatory bodies via online verification tools and audits.

The respondents also raised a number of challenges in the implementation of track and trace systems, including the availability of resources, lack of recognised standards for developing the system, requirements for drafting track and trace legislation, and tobacco industry interference.

Parties also indicated technical areas for which support would be needed to ensure implementation at domestic level, including system financing, procurement practices, IT requirements and system design, financial and human resources for implementation, and interagency cooperation.

This good-practice-gathering exercise by the working group, in cooperation with the FCTC Secretariat, is an ongoing one.

At MOP3, the Secretariat will report new findings relating to existing track and trace systems, using a new questionnaire supported by a review of information in the public domain and virtual interviews with selected parties.

The full Protocol text is available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/80873/9789241505246_eng.pdf;jsessionid=3AC1D04EFC537BF59D41D6C798062961?sequence=1.

1 - https://storage.googleapis.com/protocol-mop3-source/Main%20documents/fctc-mop3-5-en.pdf